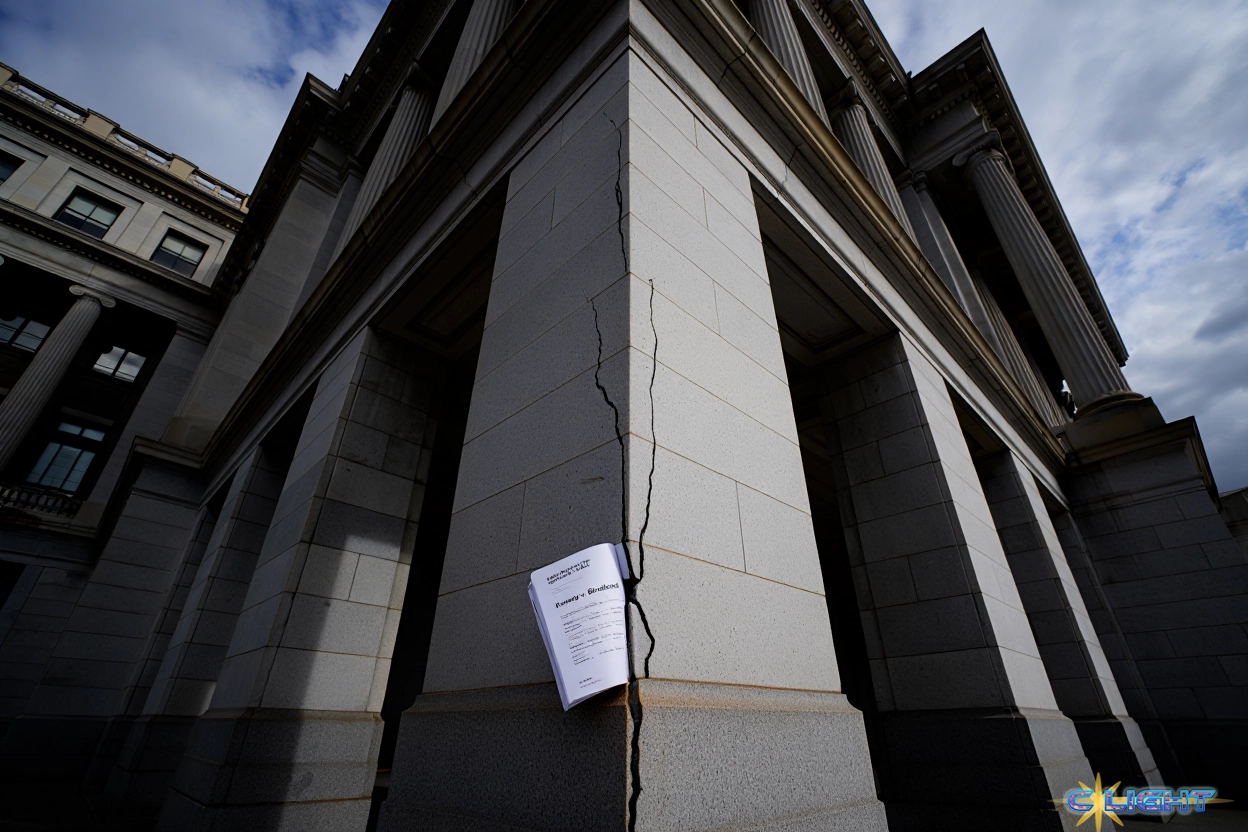

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), the legislative ghost that has haunted a decade of American politics, once again found itself before the Supreme Court. But this time, the challenge was not a grand, frontal assault on the individual mandate or the existence of federal subsidies. Instead, in Kennedy v. Braidwood Management, Inc., opponents of the law mounted a quieter, more technical, and insidiously clever attack, targeting not the edifice of the law itself, but the bureaucratic architects who design its interior. The case was a masterclass in administrative lawfare, a high-stakes legal battle over the Appointments Clause of the Constitution that threatened to detonate one of the ACA’s most popular and impactful provisions: the requirement that insurers cover a wide range of preventive health services at no cost to the patient.

At stake was the very existence of no-cost cancer screenings, contraception, cholesterol tests, and HIV-prevention drugs (PrEP) for more than 150 million Americans. In a 6-3 decision that will be celebrated by public health advocates and lamented by conservative legal theorists, the Supreme Court upheld the structure of the program, preserving the preventive care mandate and handing the ACA yet another improbable victory.

The ruling, authored by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, is a deep dive into the arcane but essential distinctions of constitutional structure. It affirms that the members of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)—the independent body of medical experts whose recommendations trigger the no-cost coverage mandate—are constitutionally appointed. But more than that, the decision reveals the modern battlefield on which the fate of major legislation is decided: not in broad strokes of constitutional philosophy, but in the fine print of bureaucratic design and the intricate mechanics of the administrative state.

The Legal Battleground: An Arcane Clause with Life-or-Death Consequences

To understand the gravity of the Kennedy case, one must first appreciate the elegant simplicity of the ACA’s preventive care provision and the arcane complexity of the legal challenge against it. The ACA mandates that private insurers must cover any preventive service that receives an “A” or “B” rating from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, without charging patients any co-pay or deductible. This provision has been revolutionary, removing financial barriers to early detection and treatment for dozens of conditions.

The plaintiffs, led by Braidwood Management, a company owned by conservative activist Steven Hotze, did not argue that preventive care was a bad idea. Instead, they mounted a structural attack based on the Appointments Clause of Article II of the Constitution. This clause dictates how “Officers of the United States” must be appointed. It creates two tiers: “principal” officers, who must be nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate, and “inferior” officers, whose appointment Congress can vest in the heads of departments (like the Secretary of Health and Human Services).

The challengers’ argument was that the members of the USPSTF wield such immense power—effectively mandating that the entire American healthcare insurance industry spend billions of dollars—that they are, for all intents and purposes, “principal” officers. Yet, they are appointed by the Secretary of HHS, not the President. Therefore, the plaintiffs argued, their appointments are unconstitutional, and all the coverage mandates that have flowed from their recommendations since 2010 are void. It was a brilliant legal maneuver: by attacking the appointment process of an obscure task force, they sought to gut one of the most popular pillars of the ACA.

The Majority Opinion: Upholding the Chain of Command

Justice Kavanaugh, writing for a 6-3 majority that included Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Barrett alongside the court’s three liberals, rejected this challenge. The opinion is a methodical defense of the existing administrative structure, focused on a single, dispositive principle: political accountability.

The majority’s reasoning hinges on the determination that the members of the USPSTF are, in fact, “inferior” officers, not principal ones. The key to this distinction, Kavanaugh argues, is supervision. Who has the power to direct and, if necessary, remove these officers? The Court found two clear lines of authority that subject the Task Force to the control of the Secretary of HHS, a principal officer who is himself accountable to the President.

First, the Secretary of HHS has the power to remove members of the Task Force at will. This at-will removal power, the Court reasoned, is the ultimate tool of supervision. An officer who serves at the pleasure of a Cabinet Secretary cannot be said to be operating without a superior.

Second, and perhaps more crucially, the Court found that the Secretary also has the power to review and effectively block the Task Force’s recommendations before they become binding. While the statute describes the Task Force as “independent,” the ACA also stipulates a waiting period between when a recommendation is made and when the coverage mandate takes effect. During this interval, the majority argued, the Secretary can direct that a recommendation not be considered “in effect,” thereby preventing the mandate from triggering. This power of review ensures that the Task Force’s decisions are not final and are subject to the oversight of a politically accountable official.

In the majority’s view, this structure preserves the constitutional chain of command. The experts on the Task Force make recommendations, but their power is subordinate to the HHS Secretary, who in turn serves the President. The line of accountability from the Task Force to the American people, running through the executive branch, remains unbroken. The challenge, therefore, fails.

The Dissent: A Warning on Unchecked Power

Justice Clarence Thomas, in a dissent joined by Justices Alito and Gorsuch, offered a starkly different interpretation. The dissenters argued that the majority’s focus on the formal lines of supervision ignores the functional reality of the Task Force’s immense power.

In their view, a body that can, with a single recommendation, re-order the priorities of a multi-trillion-dollar industry and impose binding requirements on every private insurer in the nation cannot plausibly be described as “inferior.” The dissent argued that the majority’s interpretation of the Secretary’s power to block recommendations was a strained reading of the statute, contending that the law’s description of the Task Force as “independent” should be taken at face value.

The dissent’s core concern is with the delegation of what it sees as a legislative, or at least a principally executive, power to an unelected, unaccountable body of experts. To the dissenters, the majority’s decision “distorts Congress’s design for the Task Force,” transforming it from an independent body into a subordinate one to save it from constitutional challenge. This, they argue, blesses an unconstitutional delegation of power that insulates major policy decisions from the democratic process.

The Real-World Implications: A System Preserved

While the legal arguments are dense and technical, the real-world consequences of the ruling are profoundly simple and deeply personal for millions of Americans. By upholding the Task Force’s structure, the Supreme Court has preserved, for now, the ACA’s system of no-cost preventive care.

A ruling for the challengers would have been catastrophic for public health and family finances. Insurers would have been immediately freed from the obligation to cover dozens of critical services without cost-sharing. Patients would have suddenly faced co-pays and deductibles for routine mammograms, colonoscopies, blood pressure screenings, and vaccinations. Access to vital medications like PrEP, which has been instrumental in reducing the spread of HIV, would have been severely curtailed for those unable to afford it.

The decision is a massive victory for patients, public health advocates, and the stability of the health insurance market. It ensures that the principle of preventive care—that it is both more humane and more cost-effective to prevent a disease than to treat it—remains a cornerstone of American healthcare policy.

The War of a Thousand Cuts

The Kennedy v. Braidwood Management decision marks at least the ninth time the Affordable Care Act has survived a significant challenge at the Supreme Court. It serves as a powerful testament to the law’s resilience, but also as a stark reminder of the relentless legal war being waged against it.

The era of grand, existential challenges to the ACA may be over. In its place, we have entered an era of a thousand cuts—a protracted war of attrition fought in the arcane trenches of administrative law. Opponents of the law, having failed to repeal it legislatively or strike it down on broad constitutional grounds, will continue to probe for structural weaknesses, procedural flaws, and constitutional technicalities.

For today, the law and the millions of Americans who depend on its protections can breathe a sigh of relief. The system of preventive care has been preserved. But the decision is also a clear signal that the future of American healthcare policy will be determined not just by votes in Congress, but by obscure legal battles over the separation of powers and the very nature of how our government is allowed to function. The war is far from over; it has just become more complicated.

Discover more from Clight Morning Analysis

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.