The headline landed with the disorienting thud of a time-traveler’s misstep. Six Americans were detained on a heavily militarized South Korean island for attempting to send 1,600 plastic bottles filled with rice, Bibles, and USB sticks across the sea to North Korea. Reading the dispatch, one could be forgiven for blinking and wondering, what decade are we in? The image it conjures feels less like a 21st-century geopolitical event and more like a ghost story from the height of the Cold War, a faint echo of a bygone era of high-stakes, low-tech information warfare.

But this is not a story from another time. It is a story for our time, one that reveals how the core conflicts of the 20th century persist, updated with 21st-century tools. To truly understand the gravity and the strange, nostalgic power of this incident, one must look past the police blotter and into the heart of the people who would undertake such a mission. One has to understand the kind of profound, unshakeable conviction that drives ordinary people to take extraordinary, life-threatening risks in the service of a higher calling. For me, that understanding began in a converted World War II barracks in Towanda, Kansas.

When I was about six months old, my father became the pastor of a tiny church in that converted barracks, his longest pastorate. Among the 40 or so congregants were a young basketball coach, Bill Sergeant, his wife, Laveta, and their son, Curtis, who was my age. In a town that small, our families became close. Bill and Laveta were called to the mission field, and eventually, their faith took them to South Korea. Every four years, they would return home to renew their visas, their visits filled with stories that felt more like spy novels than missionary reports. Bill, a keen amateur photographer, had managed to sneak pictures of the DMZ out of the country, contraband that could have seen him imprisoned by the South or shot as a spy by the North. Their stories were dramatic tales of clandestine hand-offs at the edge of the world’s most dangerous border, smuggling not state secrets, but scraps of the Korean-language Bible. To a young boy, hearing of this tall, stilts-like American basketball coach defying two armies to get information into the Hermit Kingdom was better than knowing Jackie Chan. It was real. This deep, personal conviction, the belief that one has a moral duty to act, is the essential, often-missed context for understanding the recent headlines from Gwanghwa Island.

Deconstructing the Modern Payload

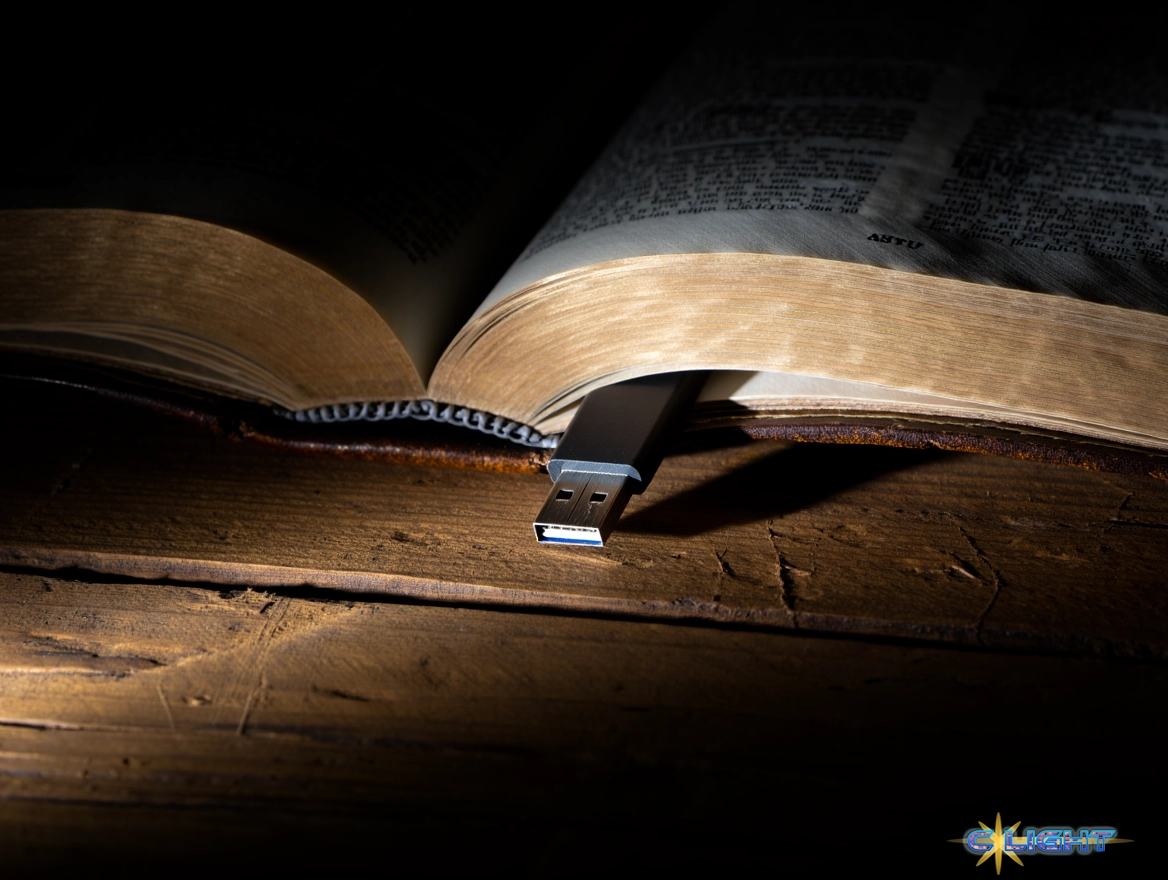

The story of the Sergeant family, smuggling Bible fragments piece by piece, serves as a powerful bridge to understanding the cargo found in those 1,600 plastic bottles. The mission is the same, but the payload has evolved, representing a sophisticated, multi-front assault on the legitimacy of the North Korean regime. This is not a random collection of items; it is a carefully curated trinity of survival, ideology, and information.

First comes the attack on the body. The inclusion of rice and U.S. dollar bills is the most basic and perhaps most profound form of subversion. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is a state built on the foundational myth of the Party as the ultimate provider, the sole source of sustenance for its people. To send rice is to send a simple, powerful message: your state is failing in its most fundamental duty. The dollar bills serve a similar purpose. In a collapsed command economy, a stable, trusted currency—even a single dollar bill—represents an alternative system of value, a tangible piece of the outside world that works. It is a direct refutation of the state’s economic narrative.

Next is the assault on the soul. The miniature Bibles are the direct descendants of the scraps the Sergeants once smuggled. This is the classic ideological challenge, a throwback to the great power conflicts of the 20th century. It offers a complete alternative, moral and spiritual framework to the state-mandated cult of personality surrounding the Kim dynasty. In a nation where the ruling family is treated with a reverence bordering on deification, the introduction of a belief system that posits a higher authority is an act of supreme ideological rebellion. It directly attacks the state’s monopoly on faith and devotion.

Finally, and most potently, there is the assault on the mind. The USB drives are the modern evolution of the missionary’s leaflet, the Cold War spy’s radio broadcast. While authorities have not officially disclosed their contents, decades of similar campaigns by activist groups and North Korean defectors give us a clear picture of what they almost certainly contain: a devastating cocktail of “soft power.” This includes South Korean dramas that depict a world of unimaginable prosperity, freedom, fashion, and romance—a direct contradiction of the state propaganda that paints South Korea as a destitute American puppet state. It includes K-pop music videos that showcase a vibrant, expressive youth culture that stands in stark contrast to the rigid, militarized conformity demanded in the North. And it likely includes an offline, Korean-language version of Wikipedia, a searchable repository of world history, science, and culture that offers a direct alternative to the state’s fabricated and heavily redacted version of reality. This is sophisticated information warfare, designed not to win a battle, but to erode the foundational myths of the DPRK from within, one mind at a time.

The Diplomat’s Dilemma: A New Sheriff in Seoul

The actions of these six American activists, however deeply convicted, did not occur in a vacuum. They crashed headlong into the delicate, high-stakes diplomatic gambit of a new South Korean government, transforming their mission from an act of liberation in their eyes to an act of sabotage in the eyes of Seoul.

Since taking office in early June, the new liberal government of President Lee Jae Myung has made diplomatic re-engagement with North Korea its signature foreign policy objective. His administration has explicitly promised to de-escalate tensions, halting provocative actions like the loudspeaker propaganda broadcasts across the DMZ in a concerted effort to create an environment where long-dormant talks with Pyongyang might resume.

From the perspective of the Blue House in Seoul, the activists’ bottles are a direct threat to this fragile peace initiative. History has shown that North Korea reacts to these launches with predictable fury, responding with “fiery rhetoric” and its own provocative acts, such as the bizarre spectacle of launching balloons filled with trash and filth into the South. For President Lee, every bottle that floats north is a potential diplomatic torpedo, capable of sinking his entire strategy before it ever leaves the harbor.

This created a legal and political dilemma. In 2023, South Korea’s Constitutional Court struck down a nationwide ban on sending leaflets and other materials to the North, correctly identifying it as an excessive restriction on the fundamental right to free speech. A new, heavy-handed law would meet the same fate. Instead, President Lee’s government has deployed a far more clever legal scalpel. Rather than a blanket ban on the content of the speech, they are using existing “safety and disaster” laws, and, more pointedly, issuing specific “administrative orders” to declare the sensitive border areas as restricted “danger zones.” This brilliant maneuver allows the government to detain the activists not for what they are trying to say, but for where they are trying to say it from. It is a far more legally defensible position, one that effectively bypasses the Constitutional Court’s earlier ruling by reframing the issue from one of free speech to one of national security and border management.

The Unresolvable Conflict

The result of this collision of interests is a classic geopolitical triangle, a tense, unresolvable conflict between three legitimate, competing claims.

First, there is the raw conviction of the activists. Whether one agrees with their methods or their message, it is undeniable that they, like Bill Sergeant decades before them, are operating from a place of profound moral and religious certainty. They believe they are answering a higher calling to provide physical relief and spiritual and intellectual truth to a captive population. And, in the eyes of South Korea’s own highest court, their right to express these views is, in principle, constitutionally protected.

Second, there is the sovereign interest of South Korea. President Lee’s government has a fundamental duty to protect its citizens—especially the millions living within artillery range of the DMZ—from a potential military escalation. It has the sovereign right to set its own foreign policy and to take what it deems to be the necessary steps to pursue peace and stability on the peninsula. The government’s duty to prevent a war arguably outweighs its duty to facilitate any single act of protest, no matter how well-intentioned.

Finally, there is America’s diplomatic tightrope walk. The United States finds itself in the unenviable position of having to protect its own citizens abroad while simultaneously respecting the laws and sovereign diplomatic objectives of a critical ally. The State Department’s decision to cancel the Seargents’ mission in the 1980s because it was deemed too dangerous provides a powerful historical parallel to the quiet, procedural approach being taken today. The public anonymity of the six detained Americans is not a sign of a conspiracy, but a function of international law—specifically the U.S. Privacy Act—and standard diplomatic procedure. Behind the scenes, diplomatic channels are certainly buzzing. This is being handled not as a common crime, but as the sensitive international incident that it is.

The Echo in the Bottles

As they float silently on the tides between two worlds, the 1,600 plastic bottles carry a cargo far heavier than rice and paper. They carry the ghosts of past conflicts and the echoes of missionaries like Bill Seargent. They carry the anxieties of a new government in Seoul attempting to chart a perilous course toward peace. And they carry the digital seeds of a potential new future for the people of North Korea, a future the regime in Pyongyang is desperate to prevent.

The technology of this clandestine war has evolved dramatically, from Bible fragments painstakingly smuggled across a fortified border to terabytes of data launched in a disposable water bottle. But the fundamental human drama remains unchanged. It is the timeless, irresistible story of deeply held conviction pushing against the unyielding walls of a closed and fearful state. The headlines will focus on the diplomatic incident, the arrests, and the legal maneuvering. But the real story is in the enduring, irresolvable tension between the individual’s moral imperative to act and the state’s pragmatic need for order. The questions these bottles ask have no easy answers, and for the foreseeable future, they will continue to float on the dark, uncertain waters of the Korean peninsula.

Discover more from Clight Morning Analysis

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.