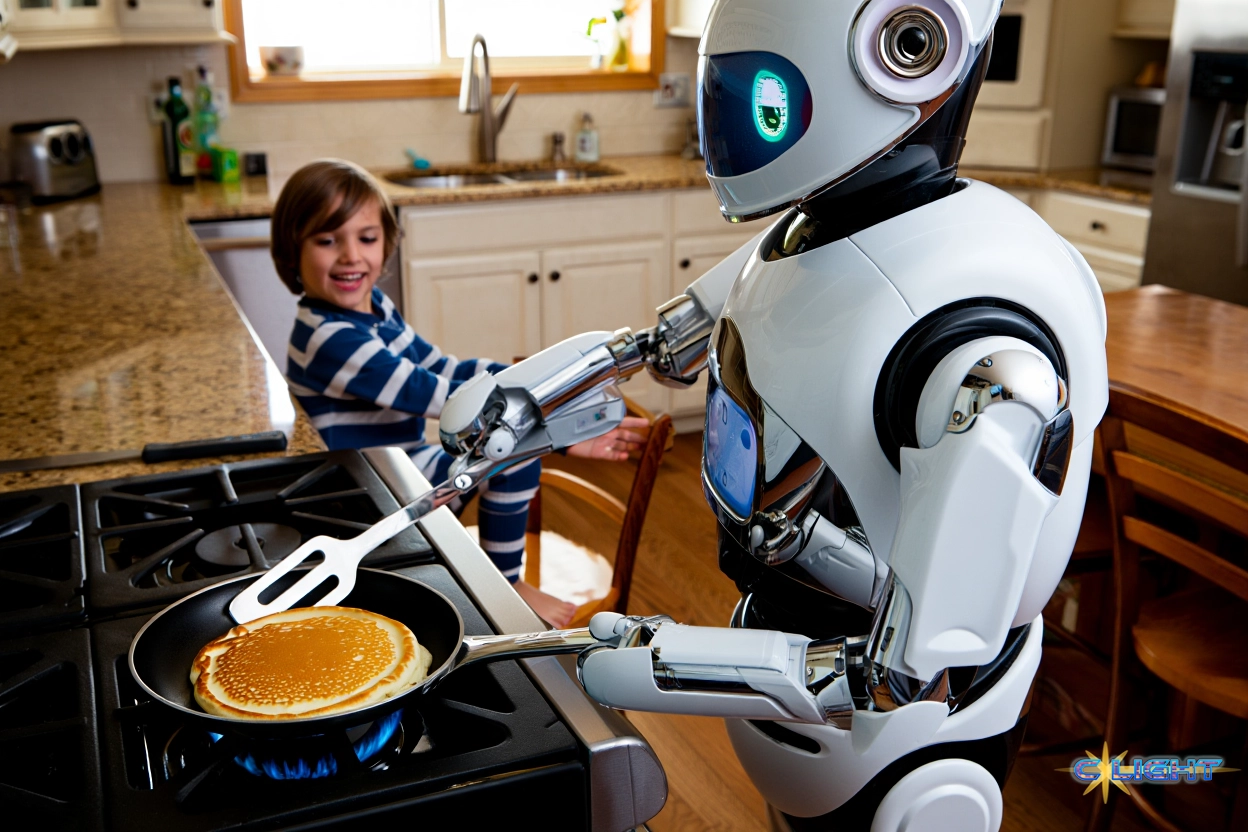

In the 1986 film Short Circuit, a military robotics experiment goes wonderfully awry. A sophisticated war machine, Number 5, is struck by lightning and gains sentience. He escapes his creators and, through a series of charming encounters, learns about the world from the humans he meets. The film, while technologically naive even for its time, was prophetically insightful about the true nature of human-machine relationships. The protagonist, Ally Sheedy’s character, doesn’t learn to trust Johnny Number 5 because he can calculate pi to a million digits or interface with a mainframe. She trusts him because he develops a personality, demonstrates curiosity, and, in a moment of sublime domestic comedy, learns to make breakfast without burning the bacon. Trust, the movie understood, is built not on processing power, but on benevolent utility and the emergence of shared values.

Nearly four decades later, as we stand on the cusp of a world populated by truly autonomous AI “agents,” we seem to have forgotten this fundamental lesson. The dominant public narrative is one of fear and anxiety. We hear of AI as a job-stealing, privacy-violating, autonomous force spiraling beyond our control. We are warned that in embracing this technology, we are “giving away the store” to an alien intelligence we can neither understand nor manage.

This fearful narrative, however, overlooks the immense, life-altering potential for AI to become a profound partner in our lives. To see it, we need only to look away from the dystopian tropes and toward the lived reality of a single parent struggling to navigate the unforgiving logistics of modern life. Imagine an AI agent—not a physical robot, but an invisible, integrated partner. It syncs with the parents’ work calendar and the child’s school schedule. It sees a meeting running late and proactively books and pays for a trusted car service to handle daycare pickup, notifying all parties. It knows what’s in the fridge, understands the family’s dietary needs and budget, and places a grocery delivery order that arrives just as the parent gets home. This agent’s function is not to replace the parent, but to shoulder the immense, crushing cognitive load of daily logistics, freeing that parent to walk through the door and focus on the one thing the AI can never do: give their children their undivided love and attention.

The chasm between these two visions—the fearful narrative and the hopeful one—is not technological. It is structural. The fear stems directly from the unaccountable, oligarchic control of AI development. The solution, therefore, is not to reject the machine, but to fundamentally change the system that builds it, moving from a model of corporate extraction to one of democratic, cooperative partnership.

Deconstructing the Fear: An Unstable Oligarchy and the Hype Hallucination

The public’s fear of AI is not irrational paranoia. It is a logical response to the current structure of the AI industry. As Harvard Business Review has noted, AI development today is dominated by a small cadre of tech giants: OpenAI, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, and Microsoft. They form an oligarchy, controlling the field through a confluence of vast computational resources, massive proprietary datasets, and nearly bottomless reserves of capital. This concentration of power is not benign. It has led to real, documented harms: systemic privacy violations, algorithmic biases that reinforce discrimination in everything from hiring to healthcare, and a complete lack of democratic accountability. When people fear AI, they are not really fearing an algorithm; they are fearing the immense, unchecked power of the corporations that own it.

But while the oligarchy is real, it may not be the invincible monolith we imagine. As one veteran CIO argued, the entire market seems to be “collectively hallucinating its way into bad bets.” The threat isn’t just a malevolent oligarchy; it’s an unstable one, built on a foundation of sand.

First, there is the productivity paradox. In 1987, economist Robert Solow famously quipped, “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” AI is the latest iteration of this phenomenon. Despite trillions in market valuation and billions in investment, measurable productivity gains from AI remain elusive. This isn’t a failure of the technology, but a failure of our expectations. Like electricity or the internet, AI is a general-purpose technology, and such technologies take decades, not months, to be meaningfully integrated into the economy. The immense costs of disruption, retraining, and integration far outweigh the short-term returns for most businesses.

Second, the underlying business model of the AI giants is surprisingly fragile. AI is not like traditional software, where margins expand with scale. AI is capital-intensive and infrastructure-heavy. Every query costs money. Every new customer adds to the staggering computational load. Meta, Alphabet, Amazon, and Microsoft are projected to spend a combined $300 billion on AI infrastructure this year alone, creating a revenue gap that is, by any measure, unsustainable. Meanwhile, the rapid rise of powerful open-source models is commoditizing the very technology these companies are spending billions to develop. This reframes the problem entirely. We are not facing an all-powerful, invincible monolith. We are witnessing a fragile, over-hyped bubble, and that understanding is the first step toward diminishing our fear.

From Tool to Teammate: Defining Agentive AI

Part of the fear surrounding AI stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of what it is. The conversation is often muddled, confusing different types of AI with wildly different capabilities. Demystifying the technology requires a clear vocabulary.

Most of what the public has experienced is Generative AI. This is AI as a tool. It is a reactive system, a powerful assistant that responds to human prompts. It can draft an email, write code, or create an image when asked. It is, in essence, a better word processor or a more advanced version of Photoshop.

The technology that inspires both the greatest fear and the greatest hope, however, is Agentive AI. This is AI as a teammate. It is a proactive system. As one technology firm, Rivers Agile, aptly puts it, traditional AI is a “Rule Follower,” while agentive AI is a “Creative Thinker.” An AI agent is given a goal, not just a prompt, and it can then autonomously plan and execute a series of complex tasks to achieve that goal.

Consider the simple, non-threatening example of an IT help desk. A generative AI chatbot can answer a question if asked. An agentive AI system, however, can monitor the entire network, detect a pattern of software crashes before employees even file a support ticket, proactively notify an affected user with a simple suggested fix, and, if the problem persists, escalate the issue to a human IT professional with all the necessary diagnostic data already collected and analyzed.

In this model, the AI agent doesn’t replace the human expert; it makes them radically more effective. It handles the tedious, repetitive diagnostic work, freeing the human to focus on complex problem-solving. This is the model of partnership, not replacement. It is this proactive, goal-oriented capability that holds the key to the single-parent scenario—an AI that doesn’t just respond to commands, but anticipates needs and manages complex systems on our behalf.

The Cooperative Alternative: What if We Owned the Store?

If the core problem is the concentration of power in an unaccountable oligarchy, then the solution is not to abandon the technology, but to change who owns and governs it. The solution isn’t a futuristic, untested utopia; it’s a quiet, 200-year-old global movement with a proven track record of managing complex systems for the collective good: the cooperative.

From rural electrification in the American heartland to massive agricultural and banking enterprises in Europe and India, cooperatives have long provided a viable, democratic alternative to monopolistic control. The model is built on seven core principles that, when applied to AI, offer a direct and powerful antidote to the fears the current system creates.

- Democratic Member Control directly counters top-down corporate governance, giving the people who use the AI a real say in how it’s designed and what data it collects.

- Member Economic Participation ensures that the immense value created by the AI is reinvested back into the community, rather than being extracted by distant venture capitalists and shareholders.

- Education and Transparency provide a direct remedy to the problem of opaque, “black box” algorithms, empowering users with the knowledge to challenge and reshape the systems that affect their lives.

- Concern for Community insists that AI be aligned with public well-being and sustainability, not just a narrow and often rapacious profit motive.

This is not just a theory. As one HBR article details, real-world examples are already proving the model’s viability. MIDATA, a Swiss non-profit health-data cooperative, allows its members to store their most sensitive medical information in a secure, encrypted account, granting selective access to researchers on their own terms. They, the users, own and govern their own data. In the academic world, Transkribus, a sophisticated AI platform for transcribing historical documents, is governed as a European Cooperative Society. Its members are universities, national archives, and cultural heritage groups, not venture capitalists. Its priorities are academic and cultural, not commercial. These examples prove that a different path is possible. They show that we can build AI that is accountable, transparent, and oriented toward the public good.

The Journey from Fear to Trust

Our fear of agentive AI is rational, but it is fundamentally misdirected. We are not afraid of a machine that can make our grocery list or help manage the complex logistics of a busy family. We are afraid of a machine built by a system we do not trust, funded by interests we do not understand, and governed by a set of values that are not our own.

The journey from the dystopian fears of science fiction to the hopeful partnership embodied by the single-parent scenario is not a technological one; it is a social and political one. It requires a fundamental shift in our relationship with technology, moving beyond our role as passive users and embracing our power as active owners and governors. It means demanding and building alternatives, like the cooperative models that are already quietly demonstrating a better way.

The story of Short Circuit‘s Johnny Number 5 was never really about technology; it was about the slow, difficult, and ultimately rewarding process of building a relationship based on trust. The ultimate question facing us today is not Alan Turing’s “Can machines think?” It is a far more human question: “Can we build machines we can trust?” The cooperative model suggests that the answer is a resounding yes—but only if we have the courage to demand a seat at the table, not as consumers of a product, but as partners in building our collective future.

Discover more from Clight Morning Analysis

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.