From the ubiquitous smartphone nestled in one’s pocket to the silent revolutions of electric vehicles and wind turbines, the sinews of modern technology are woven from a clandestine group of elements: rare earth minerals. These seventeen crucial metals, despite their misleading moniker (they are not, in fact, rare, merely difficult to extract), are indispensable components in nearly everything that hums, glows, or spins in our digitized world. Yet, the story of their procurement is not one of seamless innovation, but of scarred landscapes, poisoned waters, and a geopolitical chokehold that threatens the very supply chains upon which our technological future depends. This analysis delves into the grim realities of rare earth mining, the strategic dominance of a single nation, and the desperate, often paradoxical, efforts by Western powers to reclaim a piece of this dirty, yet indispensable, business.

China’s Monopoly: A Pyrrhic Victory of Environmental Devastation and Geopolitical Control

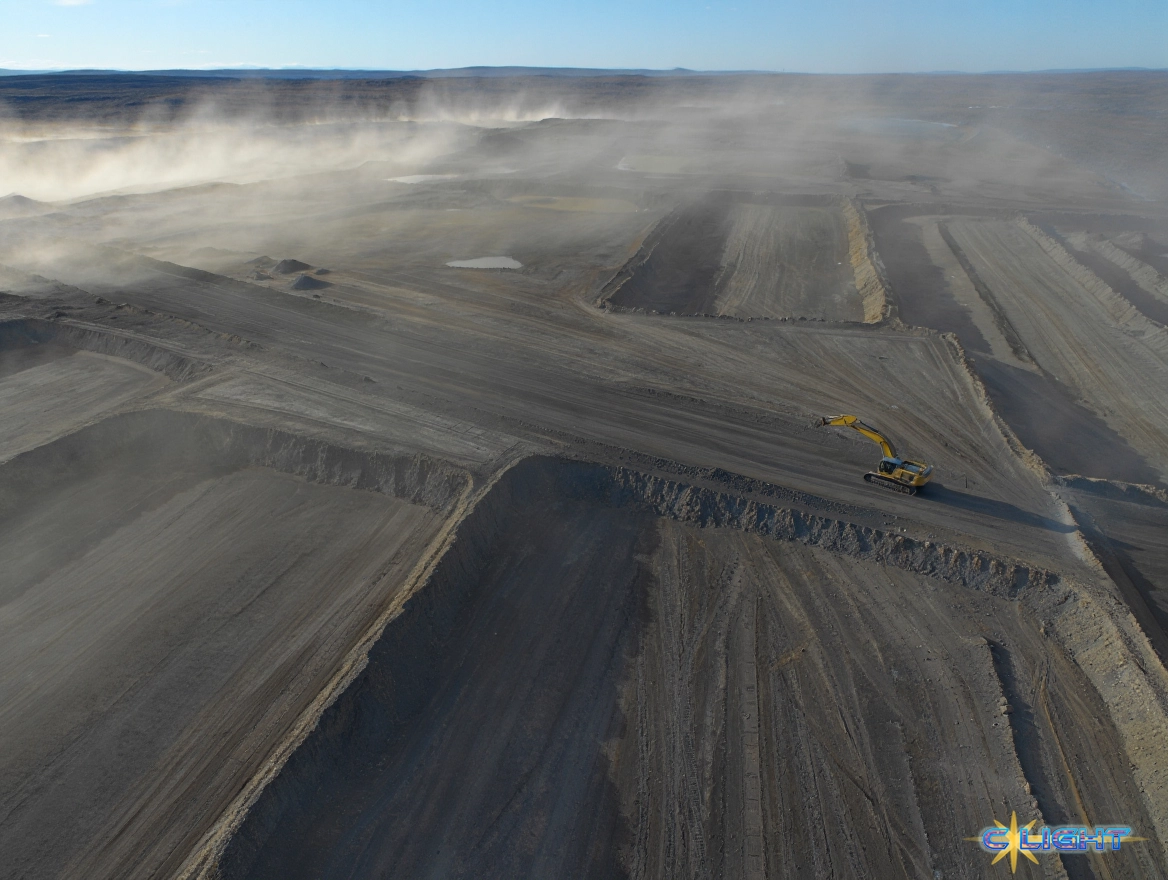

When one stands on the edge of Bayan Obo, in Inner Mongolia, China, the scale of the environmental devastation wrought by the pursuit of rare earths is starkly apparent. Here, the earth’s crust has been “sliced away over decades,” leaving an “expanse of scarred grey earth” and “dark dust clouds” rising from deep craters. This district alone houses half of the world’s supply of rare earths, a testament to China’s decades-long, relentless drive to become the dominant producer. This dominance confers upon Beijing immense leverage, both economically and politically, a power wielded in negotiations, such as those with Felonious Punk (Donald Trump) over tariffs. However, this geopolitical advantage has come at a truly staggering cost.

The environmental price paid by China is visceral and alarming. In both Bayan Obo and Ganzhou, the country’s main rare earth mining hubs, the landscape is marred by “man-made lakes full of radioactive sludge” and “small, circular concrete ponds full of toxic waste” sitting uncovered on eroded hilltops. These “leaching ponds” are injected with “tonnes of ammonium sulfate, ammonium chloride, and other chemicals” to extract the metals. The consequences are dire: research links these mining practices to deforestation, soil erosion, chemical leaks into rivers and farmland, and, in the decades leading up to 2010, “clusters of cancer and birth defects” in affected villages. The worst health effects were found near the Weikuang Dam, an 11km-long tailings pond filled with radioactive thorium, which studies suggest is slowly seeping into groundwater and threatening the Yellow River, a key source of drinking water. The staggering statistic that mining just one tonne of rare earth minerals creates some 2,000 tonnes of toxic waste underscores the profound environmental cost of our technological progress.

China’s approach, historically characterized as “develop first and clean up later,” has left an indelible scar. Despite recent efforts by Beijing to strengthen supervision and clean up sites, and a dramatic reduction in mining licenses since 2012, the damage is enduring. Local farmers, like Huang Xiaocong, whose land is surrounded by four rare earth sites, speak of landslides and illegal land grabs, lamenting their vulnerability. Their attempts to speak to international media are met with intimidation, with journalists being pulled over by police and held in three-hour standoffs by unidentified mining bosses. This oppressive environment highlights the human cost of China’s rare earth monopoly, where individual voices are suppressed in the pursuit of national strategic advantage. Paradoxically, these environmentally destructive operations have also brought jobs and money to local communities, creating a complex dependency on the very industry that poisons their land.

Adding a critical layer to China’s rare earth dominance is its reliance on Myanmar, particularly the war-torn Kachin state, for nearly half the world’s supply of heavy rare earths. These crucial minerals are extracted from mines in the hills of northern Myanmar, then shipped to China for processing into the powerful magnets essential for electric vehicles and wind turbines. This dependency has drawn China directly into the brutal civil war that erupted after Myanmar’s 2021 military coup, transforming the global supply chain into a geopolitical battleground.

For months, the global supply of heavy rare earths has hinged on the outcome of a fierce battle between the rebel Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the Chinese-backed military junta over the strategically vital town of Bhamo, less than 100 km from the Chinese border. China, wielding its near-monopoly over heavy rare earth processing, has issued a stark ultimatum to the KIA: cease efforts to seize full control of Bhamo, or Beijing will halt buying minerals from KIA-controlled territory. This demand, revealed by Reuters for the first time, underscores how China is explicitly “wielding its control of the minerals to further its geopolitical aims,” effectively shoring up Myanmar’s beleaguered junta, which China views as a “guarantor of its economic interests in its backyard.” Beijing has even sent jets and drones to the junta, which is increasingly reliant on airpower.

Despite China’s pressure, the KIA, a battle-hardened militia, has defied Beijing’s demands to pull back from Bhamo, confident that China’s “thirst for the minerals” will ultimately prevent a full blockade. This defiance has, however, restricted mining operations, causing Myanmar’s rare-earth exports to China to plunge by half in the first five months of 2025, sending prices of dysprosium and terbium skyrocketing. The battle for Bhamo has come at a high human cost, with relentless airstrikes devastating large parts of the town, killing civilians, including children, and destroying schools and places of worship. This grim reality highlights the profound human impact of the geopolitical struggle for control over these indispensable resources.

The West’s Reckoning: A Desperate Scramble for Diversification

For decades, Western powers, including Europe and the United States, willingly “outsourced much of the pollution-heavy production to China,” comfortable with the economic efficiency of letting others bear the environmental and social costs. Now, however, the chickens have come home to roost. European policymakers have become “painfully aware that Beijing has the continent in a chokehold,” with about 98 percent of the bloc’s rare earth imports originating from China (compared to 80 percent for America). The recent curbing of global access to rare earths and permanent magnets by China, ostensibly in response to American tariffs and other trade tensions, has served as a stark and immediate reminder of this precarious dependency.

Europe, once a substantial player in the rare earth industry, is now desperately trying to “get back into the rare earths business,” but the barriers are “towering.” China’s formidable advantages—its technical knowledge, vast workforce, unparalleled scale, and notably “laxer environmental regulations”—make it “difficult if not impossible for European companies to rival Asian producers on cost.” As Alena Kudzko, a policy director at Globsec, succinctly puts it, “Europe understood that mining is a dirty business, so they outsourced it elsewhere. And it became this snowball effect. We made a choice decades ago, and now it would be very hard to reverse.”

Despite the daunting challenges, the current disruption is seen by some as the “kick the continent needs to start diversifying in earnest.” The European Union has passed laws and announced dozens of projects aimed at securing its future supply of critical raw materials, including rare earths, with ambitious goals: 10 percent mined, 25 percent recycled, and 40 percent processed in Europe by 2030. Companies like Solvay in France are attempting to restart production, purifying rare earth minerals like neodymium and praseodymium for use in permanent magnets. However, their efforts are tentative, with Solvay’s CEO Philippe Kehren stating they will only scale up production (a €100 million investment) if they can find customers willing to prioritize reliable, nearby supply over minimizing costs. “If we don’t have many buyers, we’re not going to invest,” he admits, highlighting the persistent tension between strategic independence and market price.

The immediate problem remains diplomatic. Since early April, China has required export licenses for rare earth minerals, and officials have been “slow to process the licenses,” causing widespread shortages and leaving European executives scrambling. Only about half of export license requests were approved as of late June, and Chinese trade officials have even demanded sensitive business information on applications. Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, has publicly accused China of “weaponizing” its quasi-monopoly, even showcasing a permanent magnet from a new Estonian factory at the G7 meeting in Canada as a symbol of Europe’s nascent efforts.

The West’s strategy is not to build a wholly homegrown industry but to diversify supply chains and embrace recycling, which is less polluting. However, rebuilding a supply chain takes time, and the question remains whether the current sense of urgency will persist if supply complications ease. As Nils Poel, head of market affairs at the European Association of Automotive Suppliers, notes, “At the C.E.O. level, yes, it’s strategic, but then, when the procurement teams come in, it’s still about price.” Yet, he observes, “There’s a little more willingness, now, to pay a premium.”

The Scarred Earth and the Strategic Imperative

The global reliance on rare earth minerals presents a profound paradox: the very elements that enable our advanced technologies are procured through processes that scar the earth, poison communities, and confer immense geopolitical leverage upon a single nation. China’s dominance, built upon decades of “develop first and clean up later” policies, has created an environmental catastrophe and a human rights dilemma, yet it remains the indispensable engine of the modern technological world.

The West’s belated scramble to diversify its rare earth supply is a testament to the strategic vulnerability created by past outsourcing decisions. While European and American efforts to restart mining, increase processing capacity, and embrace recycling are underway, they face towering barriers: the sheer scale of China’s operations, its cost advantages derived from laxer regulations, and the inherent reluctance of businesses to prioritize strategic reliability over immediate price. The ongoing “weaponization” of rare earth exports by China, now explicitly extending to influencing civil wars in its “backyard” like Myanmar, serves as a stark reminder that this is not merely an economic issue, but a matter of national security and technological sovereignty.

Ultimately, the story of rare earth minerals is a cautionary tale: the hidden costs of our technological progress, the uncomfortable trade-offs between environmental protection and economic expediency, and the enduring geopolitical consequences of unchecked industrial dominance. No matter where these metals are eventually sourced, the warning remains clear: without fundamental shifts in mining practices and a global commitment to responsible production, landscapes and lives will continue to be put at risk, leaving a permanent scar on the earth and a heavy price for our collective technological advancement.

Discover more from Clight Morning Analysis

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.