5 minutes read time.

Stalking has long been treated as a “lesser” crime, a form of violence that, because it often involves no direct physical contact, is culturally and legally minimized. It is seen as a psychological violation, a campaign of terror that leaves invisible wounds. Now, a groundbreaking new study, following over 66,000 women for two decades, has made those invisible wounds horrifyingly visible. The research, published in the American Heart Association’s prestigious journal Circulation, provides the first definitive, long-term proof that the psychological terror of being stalked leaves a lasting and potentially fatal physical scar on a woman’s heart.

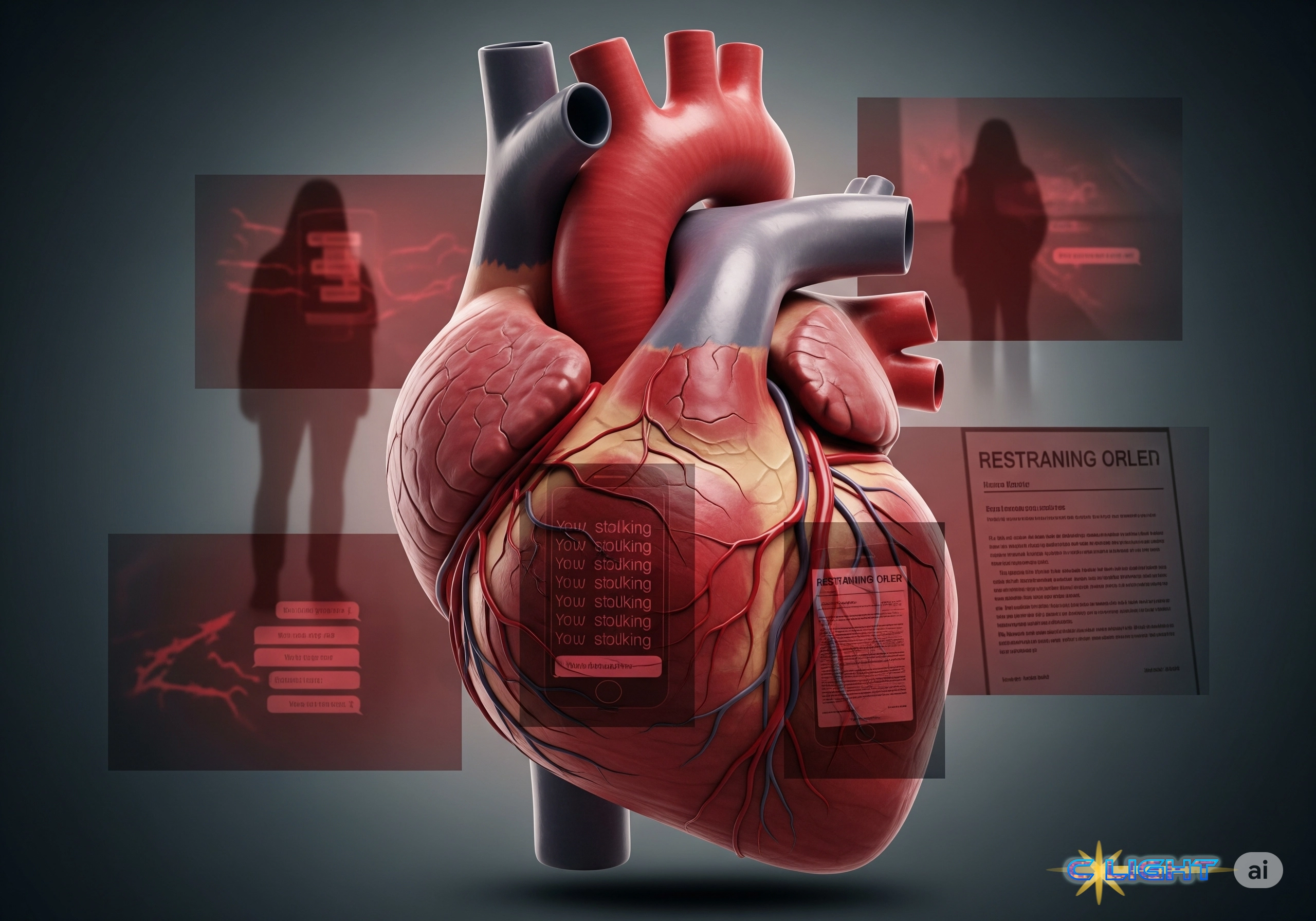

The numbers are a stark and undeniable indictment. The study found that women who reported being stalked had a 41% increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease, including heart attack and stroke, over the following 20 years. For women whose experience was so severe that they were forced to obtain a restraining order, the risk was even more catastrophic, soaring to a 70% increase. These are not just statistics; they are a 20-year echo of fear, a scientific validation of a truth that survivors have always known: the body keeps the score.

Part I: Redefining “Violence”

“Stalking can be chronic, and women often report making significant changes in response, such as moving,” said Rebecca Lawn, the study’s lead author. Her understated conclusion that stalking “shouldn’t be minimized” is the central takeaway of this research. This study forces us to redefine our very understanding of the crime. It is not just a psychological campaign; it is a long-term public health crisis with potentially fatal consequences.

The full study reveals a crucial and devastating link: the vast majority of these cases are a form of intimate partner violence (IPV). The researchers found that 71.2% of the women who reported being stalked also reported experiencing IPV, and a staggering 84.8% of the restraining orders were taken out against a spouse or significant other. The study’s authors conclude, “our findings likely represent a form of IPV for many women in our sample.” This is a critical connection. It proves that stalking is not an isolated behavior, but a key and terrifying component of the broader domestic abuse crisis, a tool of control and terror that continues long after a woman has left an abusive relationship.

Furthermore, the study found a clear “dose-response relationship” between the severity of the trauma and the physical harm. Women who had experienced both stalking and obtained a restraining order—a marker of the most severe cases—had the highest risk of all, with their risk of developing cardiovascular disease more than doubling compared to women with no such history. The message from the data is clear: the more intense and prolonged the terror, the deeper and more lasting the physical scars.

Part II: The Buried Lede – A Crisis for Vulnerable Women

As horrifying as these numbers are, the study’s own limitations, detailed with admirable scientific integrity, point to a far more disturbing and buried truth: these statistics are likely a significant underestimate of the true scale of the crisis.

The researchers state plainly that their study population, drawn from the Nurses’ Health Study II, was overwhelmingly (93.3%) non-Hispanic white women. They explicitly acknowledge that this is a major limitation, as other evidence shows that stalking is “more common among women from minority racial or ethnic backgrounds and those with low income.” They also note that women with higher income and education are “reportedly more likely to use restraining orders,” meaning the 70% increased risk for this group is a metric of the harm done to women who have the resources to navigate the legal system.

The implication is devastating. The 41% and 70% risk increases represent a best-case scenario, the damage done to a relatively privileged cohort. The true, unmeasured toll on women of color and low-income women—who are both more likely to be victimized and face greater “structural barriers” to seeking and receiving protection—is almost certainly far, far worse. This is not just a health crisis; it is a crisis of profound health inequity.

A Call to Action for a Nation in Denial

The study’s conclusion contains a direct and urgent call to action for the medical community. The authors argue that because a history of being stalked is “unlikely to be disclosed to health care providers given the lack of screening,” doctors must learn to look “beyond traditional risk factors when evaluating CVD risk” for women.

This is a necessary first step, but it is not enough. The implications of this research extend far beyond the doctor’s office. It is a call to action for the justice system, for law enforcement, and for society at large to stop treating stalking as a lesser, “non-contact” crime. This study proves it is a matter of life and death, an act of violence that can echo in a woman’s body for decades. The numbers from this study are not just statistics; they are the quantifiable shadow of terror, a long trail of fear that manifests as, quite literally, broken hearts. It is a profound and undeniable public health crisis, and it is time we started treating it as such.

Discover more from Clight Morning Analysis

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.