12 minutes read time.

The Ghost of Saturday Night

There is a particular kind of melancholy that settles in on a quiet evening, a phantom limb of a feeling for a life not quite lived. I was sitting outside with my dog last night, watching the sports cars and their young drivers peel away from the neighborhood, chasing the electric promise of a Saturday night elsewhere. For a moment, a familiar jealousy flickered—not the Fear of Missing Out, but its more wistful cousin, the Fear of Having Missed Out, in the past tense. I was raised in the church, the son of a pastor in rural Oklahoma, and my life was governed by high expectations. We did not go out on Saturday nights. We did not dance. We did not drink. We rested. We prepared for a Sunday morning that, in the mournful rhythm of its hymns and the reheated familiarity of its sermons, rarely seemed to deliver on the promise for which the preceding night had been sacrificed.

Looking back across four decades, I find myself thinking, “Too many Saturday nights were wasted ‘resting up’ for a Sunday morning that failed to deliver.” It’s not that every night was a loss. There were fleeting kisses from momentary girlfriends whose names are now lost to time, the memory of holding a young body next to mine a warm but faded ember. But there were never enough of those nights. The curfew was always ten o’clock, so that we may be well-rested for the Lord’s Day. This quiet ache, this sense of a life lived too much in the margins of a pre-written script, is not a unique affliction. It is a profound and pervasive anxiety settling over modern life, a cross-generational malaise born from the growing chasm between the lives we were promised and the ones we are actually living. For every generation, the script is failing. The promise of a secure career, a home, a stable future—these have become flimsy and uncertain plot points. In the midst of this wreckage, we are engaged in a desperate, often unspoken, search for some semblance of sanity, for something that allows us to go to bed at night with a genuine sense of peace. The solution, it seems, lies not in chasing the old promises more aggressively, but in a radical shift of perspective, a turn toward the doodles in the margins, the difficult conversations in the caves of our own making, and the quiet labor of tending to our own gardens.

The Doodle and the Defense of the “Pixillated” Soul

In Frank Capra’s 1936 film Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, the protagonist, a small-town man who inherits a vast fortune and decides to give it away to the poor, is put on trial for his sanity. The powers-that-be, aghast at his altruism, seek to have him declared insane. Witnesses describe him as “pixillated”—an old term for someone touched by pixies, or elves. The climactic courtroom scene, however, sees Mr. Deeds turn the tables. He points out the judge’s own quirky habit of filling in the O’s on a page with his pencil. He then introduces a new word for the “foolish designs on paper” people make when they are thinking: “doodling.” He reveals that the snooty psychoanalyst testifying against him is a prolific doodler himself. In this moment, the doodle becomes a great equalizer. It is the shared, irrational, non-productive quirk that proves a common humanity. The judge, recognizing this, declares Mr. Deeds “the sanest man that ever walked into this courtroom.”

As an essay in Aeon explores, this cinematic moment captures the birth of a powerful modern idea: the doodle as a subversive and democratic act. In a world increasingly defined by the cold logic of industrial efficiency and the pressure to conform, the doodle represents a defense of the illogical, the wandering, the parts of our minds that are essential for true creativity and sanity. It is, as the artist Saul Steinberg amended Paul Klee, “a thought that went for a walk.” It is non-hierarchical; presidents and toddlers, artists and inmates, all are doodlers. It requires no skill, no status, no justification. It is an act of quiet rebellion against a culture that demands every moment be productive and every action be optimized.

This defense of our “pixillated” souls is more critical now than ever. The pressures of “workism”—the modern religion that posits one’s career as the primary source of identity—have led to a world where even our leisure time has been colonized by the logic of the workplace. We are encouraged to “operationalize rest,” to fill our evenings with checklists of self-improvement tasks, a phenomenon psychiatrist Pooja Lakshmin calls “faux self-care.” We go to yoga not for the experience, but to check a box. We meditate to be more productive the next day. This relentless pressure to perform, to be constantly “on,” is a significant driver of the anxiety and burnout that plague modern life. Psychological research consistently shows that the capacity for “mind-wandering”—the very state in which doodles are born—is essential for creative problem-solving and mental well-being. By devaluing these non-linear, “wasteful” moments, we are not only stifling our creativity, but we are also undermining our own sanity. The first step toward a better life, then, is to reclaim the doodle, to fiercely defend the value of the seemingly valueless, and to recognize that our most authentic selves are often found in the messy, irrational scribbles in the margins, not in the clean, straight lines of the main text.

The Cave and the Classroom – Finding Connection in the Unlikeliest of Places

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave tells of prisoners chained in darkness, who mistake shadows on a wall for reality. It is a timeless metaphor for ignorance and enlightenment, but as another powerful essay from Aeon reveals, the “cave” is not just a philosophical concept; it is a lived reality, and the path out is far more complex than a lone philosopher returning with the truth. The essay details the experience of teaching a philosophy class inside a women’s correctional facility, bringing together incarcerated “Insiders” and traditional college students, or “Outsiders.” This classroom becomes a space where the walls of two very different caves are simultaneously tested. The Insiders are trapped in the literal prison, a world so totalizing that, as one student notes, “you start to think this is all there is.” The Outsiders, meanwhile, arrive trapped in their own cave of social media jargon, performative activism, and the echo chambers of campus life, a world of abstract theories rarely tested against hard reality.

The process of “making life better” in this incredibly challenging environment begins not with a lecture, but with a student-led ritual: a weekly “silly socks” competition. This small, humanizing act of shared absurdity creates a common culture that transcends the rigid, dehumanizing labels of “student” and “offender.” It is from this foundation of authentic connection that the real work can begin. When the class tackles Plato, the Insiders grasp the allegory with a profound, visceral understanding. But they also challenge it. One student, Jacynda, brilliantly questions the authority of the enlightened philosopher who returns to the cave: “Who are these motherfuckers, anyway? Oh lemme guess – they’re supposed to be the philosophers?” It is a moment of pure, raw, truth-seeking that cuts through centuries of academic abstraction.

What unfolds is a process of mutual liberation. The Outsiders, confronted with the lived experience of the Insiders, are forced to abandon their “pre-approved talking points” and learn to listen. The Insiders, in turn, are given the philosophical tools to analyze and articulate their own condition. The lesson is profound: we cannot escape our own caves in isolation. True enlightenment is not a solitary journey; it is a communal process of authentic, challenging, and deeply human dialogue. Sociological research has extensively documented the dangers of social fragmentation and the rise of ideological “echo chambers” in modern society. This classroom in a prison becomes a radical experiment in building “bridging social capital”—the connections between disparate groups that are essential for a healthy democracy and individual well-being. It suggests that a crucial path to a better life is to intentionally seek out and engage with people whose caves are profoundly different from our own. It is in the difficult, uncomfortable, and often revelatory space between our realities that we find a larger, more coherent truth.

The Garden and the Machine – Reconnecting with a Lost World

The modern “hell” is often a state of profound alienation. In a deeply personal and philosophical essay from Harper’s, the author Karl Ove Knausgaard diagnoses this condition as a “loss of the world.” We are so inundated with images, data, and information—a “pseudomemory from a pseudoworld”—that reality itself begins to feel “thinner,” more abstract, and less real. We see a forest fire on a screen; we know it is happening, but we are not connected to it. We stand outside, watching. This disconnection from the physical, material world is a primary source of our modern anxiety. The essay then charts a path back to reality, a journey from alienation to reconnection.

For Knausgaard, the turning point is a simple, almost mundane act: he decides to plant a garden. A space that was previously an abstract “nothing”—”the garden”—is transformed through the direct, physical labor of digging, planting, and watering. The plants go from being anonymous images to individual beings he is “deeply familiar with and cared about.” This act of tending to a small patch of earth is a form of “true leisure,” an unmeasured and non-transactional activity that reconnects him to what the artist Jenny Odell calls “the fact of your own aliveness.” It is the practical application of finding a “vertical crack” in the suffocating wall of abstract, screen-based life.

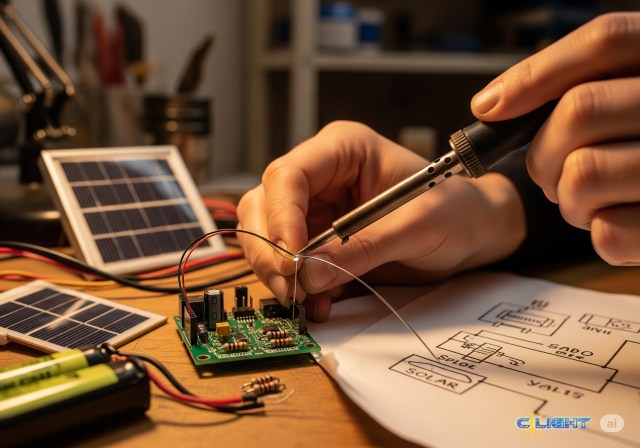

This journey leads to a more profound philosophical insight, sparked by the writer and artist James Bridle. Bridle argues that our alienation is not caused by technology itself, but by our lack of knowledge about it. We treat our devices and the systems that run our lives as magical, unknowable black boxes, which makes us feel powerless. The antidote, Bridle suggests, is to re-engage with the world through the act of making things. He recounts pulling himself out of a deep “climate depression” not by thinking, but by building—converting a camper van, creating simple solar ovens and heaters from scrap. This act of “making” did not solve the climate crisis, but it gave him a “capacity to respond” and a “feeling of competence in the face of very complex systems.”

This is a powerful and hopeful path forward. In a world of overwhelming complexity, we can fight back against the feeling of powerlessness by engaging in hands-on, tangible creation. This can be as simple as tending a garden, as creative as learning to code, or as practical as fixing a broken appliance. These activities create what psychologists call “flow states,” where we are so absorbed in a task that our anxieties and the chaotic noise of the world fall away. They are a direct refutation of our passive, consumerist culture. By moving from being a mere user to an active maker, we demystify the systems that govern our lives and reclaim a fundamental sense of human agency.

The Still Point of Integrity

The journey out of the modern malaise, then, is a multi-stage process. It begins with a rebellious act of individual agency, a refusal to be a scapegoat in a failing system. It requires the wisdom to reject the false promise of optimized productivity and the courage to seek out authentic human connection, especially with those outside our own caves. It finds its practical expression in the tangible, grounding act of making and tending, of re-engaging with the physical world. But all these paths ultimately lead to the cultivation of a single, foundational virtue: integrity.

The essayist Peter Wehner defines integrity by its Latin root, integer, meaning “wholeness.” A person of integrity is not a perfect being, but one who possesses an “inner harmony,” a coherence between their values and their actions. They are, in the words of T. S. Eliot, a “still point in a turning world.” This is the ultimate answer to the problem of a world “going to hell.” External chaos loses much of its power to destroy us when we have a strong, coherent, and harmonious inner world. The cultivation of integrity is the process of building that inner sanctuary. When we choose to doodle instead of optimize, to engage in difficult dialogue instead of retreating to our echo chambers, to plant a garden instead of scrolling through images of them, we are performing small, practical exercises in building that wholeness. We are aligning our actions with a deeper set of values, forging a self that is resilient to external pressures. The quiet ache of those wasted Saturday nights is the longing for this very authenticity. The great challenge, and the great opportunity, of our chaotic times is to finally answer that call—to build a life of such sturdy, internal coherence that we can, at last, create our own Sunday morning, and find that it finally delivers.

Discover more from Clight Morning Analysis

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.