9 minutes read time.

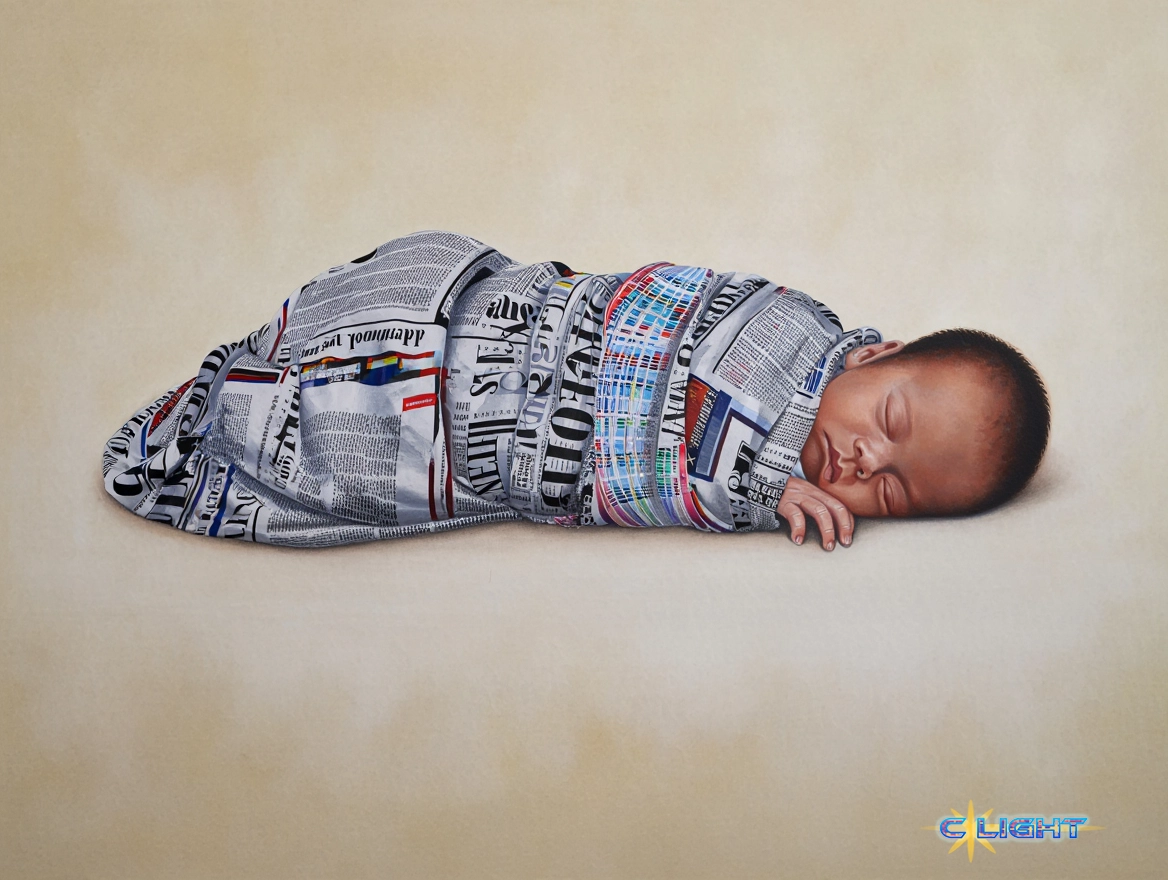

It began with a simple, unsettling thought at the end of a violent week: perhaps we are all born with a form of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. After all, the very act of giving birth is itself a form of violence. Our first experience as humans, passing through the birth canal and being shoved out into the light and noise of the “real” world, is so traumatic that our brains, in an act of profound and necessary mercy, lose the memory almost as quickly as the event happens. Our first act as humans is to shut away the pain that brought us here, to begin our lives with an unremembered wound.

This is not just a poetic metaphor; it is a story that has shaped my own family. I was born in 1960, in a standard maternity ward where my father could only view me through nursery glass. For my mother, a small woman, my arrival was a physical trauma so severe that her doctor advised her not to have any more children. But this was an era before reliable birth control, an era where “interfering with God’s plan” was a powerful social deterrent. Four and a half years later, my legally blind brother was born, and this time the doctors were firm. A hysterectomy followed, a procedure that would cause my mother health problems for the rest of her life and precipitate repeated bouts of emotional distress. We never said she was “seeing a therapist.” We just knew that there were men on the moon and Mom was sick. A lot. It was into this atmosphere of unspoken, cascading trauma that I first heard a song on the radio by the band Chicago, with a lyric that seemed to capture the very air we were breathing:

“Does anybody really know what time it is? /

Does anybody really care? /

If so, I can’t imagine why /

We’ve all got time enough to cry.”

That feeling—of disorientation, of being unmoored in a world that has ceased to make sense—is the very definition of a post-traumatic state. PTSD, I’ve come to believe, is not a new disorder; it is simply the newest name for a part of our shared human existence. For millennia, our brains developed sophisticated coping mechanisms to deal with it. The neuroscientist Dean Buonomano speaks of “mental time travel,” the cognitive leap that allowed us to plan for the future but also cursed us with the traumatic knowledge of our own mortality. “Some early humans,” he notes, “must have looked in the future and said, ‘Oh shit, I’m going to die.'” To manage this and other traumas, our brains learned to manipulate their own perception of time. Buonomano explains that our sense of the “present” is not a fixed point but a flexible “window of integration.” This neurological function is the likely basis for our psychological ability to repress trauma. In the face of horror, our brains can simply refuse to integrate the traumatic data, effectively resetting the timeline so that, in our memory, the event never happened. We are biologically wired to forget.

But what happens when a trauma is too vast, too shared, too environmental to be simply forgotten? Our brains resort to a different trick: they reframe it. They create a new narrative. After a catastrophic flood in Eastern Kentucky, multiple, unrelated people began reporting sightings of small, goblin-like creatures, consistently described as resembling “Dobby from Harry Potter.” Crucially, the witnesses were not afraid; they were “gobsmacked.” They felt compassion, a sense that these strange beings “needed help.” Their brains, unable to process the senseless destruction of their homes and communities, had created a new, manageable mystery. This is a tale as old as time. In World War II, pilots facing the horrifying stress of constant mechanical failure and the threat of death blamed “gremlins” for the malfunctions. Miners, facing the daily terror of the deep earth, told stories of “tommyknockers” who warned of impending collapse. Before we had neuropsychiatry, we had folklore, astrology, and myths—all sophisticated systems for taking a chaotic, violent reality and imposing a narrative on it to make it survivable.

It was in the shadow of the Vietnam conflict that we began to understand that these coping mechanisms have a breaking point. When trauma is repeated, again and again, delivered into our living rooms on a 24/7 news cycle, the brain’s old tricks—forgetting, reframing, finding solace in simple faith—all stop working. We have reached a point of saturation. The clinical data are terrifyingly clear. A recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association on communities that have experienced mass violence found that nearly a quarter of the entire community—not just direct survivors—met the criteria for past-year PTSD. The trauma has become an environmental toxin. And the single greatest predictor of who develops PTSD is a prior history of trauma. For a person who has already experienced physical or sexual assault, the odds of developing PTSD after a community mass violence incident are nearly ten times higher. We are no longer a society of individuals experiencing isolated traumatic events; we are a society of pre-traumatized people, where each new horror is a match thrown onto a landscape already soaked in the gasoline of our unprocessed pain.

This trauma, of course, is not equitable. The “Bloodline of Humanity,” this river of violence, floods some neighborhoods while leaving others untouched. A separate, massive study of predominantly African-American women of low socioeconomic status in Atlanta found that their lifetime prevalence of PTSD was nearly 54%—a rate higher than that of combat veterans. For this community, daily life in an American city is more traumatic than war. The study is clear that this is not an accident. It is the direct result of “social determinants of health”—poverty, systemic racism, housing instability—that we ourselves have built and maintained. We have, through our own doings, brought this curse down upon them.

And for those trapped in this cycle, the well-meaning advice to simply “turn to God” is not just inadequate; it can be another form of violence. A growing body of clinical research shows that while faith can be a source of “positive religious coping,” it can just as easily become a source of “negative religious coping” or “spiritual struggle” that makes PTSD worse. For a person whose sense of a just universe has been shattered, the rigid certainties of organized religion can feel like a cage. The demand to trust in a divine plan that seems to include the suffering of the innocent, or to forgive a perpetrator before one is ready, can become a form of psychological torture. More chillingly, for those with pre-existing “complex trauma,” often from childhood abuse, the demand of religion to accept the imperceptible can become a trigger for a full-blown psychotic episode. Research into the link between religiosity and schizophrenia has found that for individuals with insecure or disorganized attachments—a common result of early trauma—the need to project their frustrated needs onto a divine figure can lead them to embrace a fundamentalism that blurs into delusion, creating a perfect, closed loop of trauma, belief, and madness.

So where does this leave us? Our myths are violent. Our history is a forgotten trauma. Our brains are overwhelmed. Our coping mechanisms are failing. Our religions are making us sicker. It’s a dark and seemingly hopeless diagnosis. But we have been shown a different path.

There was a time, from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century, when our culture consciously tried to build a new, non-violent mythology for itself. It was an era of profound and unironic optimism, where the greatest public celebrations were not for victorious generals, but for the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge, the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, and the invention of the electric light. The heroes of this era were the “constructive heroes”—the engineers, the inventors, the scientists. Jonas Salk was “enthroned among the immortals” not for causing suffering, but for ending it. It was an era that believed in a “Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow,” a time when we celebrated the conquests of mind over matter that “cost no tears, shed no blood, desolated no lands, made no widows nor orphans.” We had the light, and then, in the cynical shadow of war and the anxiety of the nuclear age, we lost it. We forgot.

The solution, then, is to choose to remember. It is to consciously decide to break the cycle. To break the cycle of violence, break the cycle of abuse, break the cycle of slavery and racism, break the cycle of fear, and please, for the sake of all that is sane, break the cycle of calling ourselves sinners. We must accept that we arrive in this world as damaged beings and work actively to protect and heal, not to add to the trauma. We must, as the poet Shane McCrae suggests, reject the pointless, unproductive violence born of jealousy and a failure of recognition. We must, as AI is now allowing us to do with weather and agriculture, use our ingenuity not to erase our consequences, but to mitigate future suffering.

Just because we are born damaged beings doesn’t mean we have to continue as such. We can heal. We can acknowledge the hurt without feeling the need to hurt someone else in return. We can put away the need for retribution or revenge. We can choose to stand above, even if it means standing alone. We are waiting for the breaking of a new day, where we can rest our eyes and not worry that we might avoid yet another trauma-inducing moment. This moment is yours. Take it.

Discover more from Clight Morning Analysis

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.